Communism’s Misconception: The North Korean Class System

When considering communism, it is often perceived as a society that promotes equal treatment for all. However, North Korea, a self-proclaimed communist nation, exists as a highly structured society. In such a setting, one’s societal standing, life trajectory, and quality of life are profoundly dictated by one’s social class, established by their lineage or birth origin (출신성분).

Divergent Backgrounds: My Parents

My parents came from vastly different social strata. My father was born into a prosperous and highly educated family. My great-grandfather, a notable landowner in Wonsan (원산), owned an orchard. Being the eldest son, my grandfather was raised amid immense familial expectations. He pursued his studies at Meiji University in Japan, while my grandmother honed her musical skills at Tokyo University. Upon their return to Korea, they both assumed roles as educators, teaching mathematics and music respectively.

Following Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule, my grandfather sent his two younger siblings to South Korea. He had planned to follow with his wife and children, but the advent of the Korean War upset these plans. Tragically, he was killed during a bombing raid.

Within North Korea, possessing wealth as a member of the bourgeoisie was seen as highly undesirable. Wealth was often analogized with vampirism, seemingly sucking the life force out of the earnest, laborious common folk.

Worse still for my grandparents, those who had studied in Japan were targeted for purges in the early days of the regime. They were divested of their land, properties, and employment, and relegated to rural areas.

Class Shifts and Communism: The New Privileged Class

This was a situation somewhat similar to the Cultural Revolution in China. The landlords and the educated elite became targets for removal, while the uneducated serfs, now workers, came into power as the new privileged class. With the advent of the North Korean regime, the educated group, including landlords, was driven into rural areas, and those who had lived as serfs were celebrated as workers and gained power.

Family Repression: Impact of Political Purges

My father’s family, seen as undesirable due to their affluent background, was marked in red – a symbol of their bad social class status. People with wealth and education were categorized as pro-Japanese sympathizers, regardless of their actual stance or actions toward Japan. Simply leading their lives diligently, having wealth and education, and having studied abroad were enough to make them targets for purges.

Those who had been serfs gained power by becoming members of the Communist Party.

For instance, one of my elementary school teachers desired to become a member of the Communist Party, but her low social class status made this impossible. If a family had even a single landlord or elite member, it would negatively affect the family’s social class status. It became difficult to qualify to become a Party member in North Korea.

My widowed grandmother faced the same fate. She was stripped of her teaching credentials and banished to a rural village. Struggling to raise three children during the war, she retained custody of her youngest son and sent her first two children – my father and aunt – to an international orphanage in China. En route, my father and aunt were separated, and my father spent his childhood in a foreign land where he knew no one.

From Hardship to Hope: My Father’s Journey

Despite his challenging upbringing, my father nurtured a passion for learning from a young age. At 18, he returned to North Korea and enrolled in a university in Pyongyang. Residing in Pyongyang requires a favorable birth origin, and due to his grandfather’s landowner status, he had no choice but to conceal his true identity to live in the capital. When his true family background was exposed during his sophomore year, he was expelled and fled to China in pursuit of hope. However, unable to secure Chinese citizenship, he was forced to return to North Korea during a time when China faced economic struggles, and even Chinese individuals sought better opportunities in North Korea.

My father spent two years in SunBong (선봉) working as a bulldozer driver, using a falsified Korean-Chinese (조선족) ID. When it became impossible to conceal his true identity, he disclosed it. Fortunately, due to a shortage of bulldozer drivers, he avoided deportation.

An Unlikely Love Story Begins

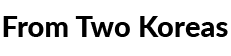

My father couldn’t marry until he was over thirty. Then, finally, he met my mother while transporting coal between the Sunbong Coal Mine in Aoji and SunBong. They married in 1979 when he was thirty-six and she was twenty-three.

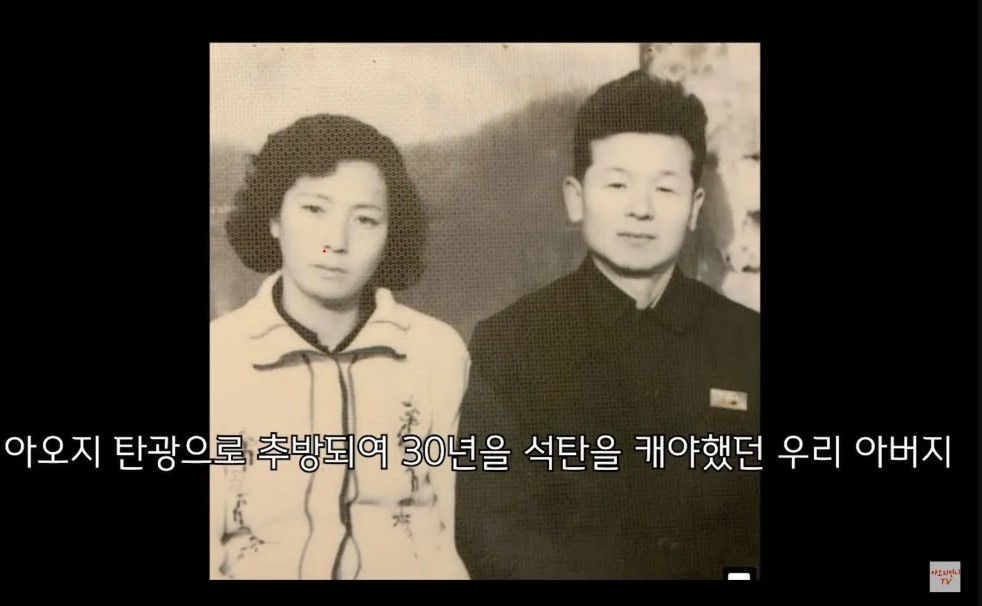

My father was smitten with my mother at first sight and went to visit her at home. In contrast to my father, my mother came from a highly respected background. In North Korea, individuals who participated in the anti-Japanese struggle are revered for their noble origins. This reverence is rooted in the historical context of Koreans’ fight for independence during Japan’s occupation and colonization of the Korean peninsula in the early 20th century.

In North Korea, people who participated in the anti-Japanese struggle are considered to have noble origins, due to the historical context of many Koreans fighting to regain their independence after Japan occupied and colonized the Korean peninsula in the early 20th century.

Those who took part in the anti-Japanese struggle are acknowledged as heroes who sacrificed and fought for their country, and their families are also honored. The North Korean government lauds them as heroes and loyalists of the revolution, bestowing upon them elevated social status and privileges. Their children benefit from excellent educational opportunities and secure crucial positions in the military and government.

The prestigious lineage of those who participated in the anti-Japanese struggle is deeply tied to the political system in North Korea, which honors and privileges their fighting spirit and sacrifices. This political system, combined with the communist ideology, contributes to maintaining political, economic, and social stability within North Korea.

My mother’s aunt, Heo Seong-sook, fought alongside Kim Il-sung in the anti-Japanese armed struggle. She is even mentioned in Kim Il-sung’s memoirs.

It seemed impossible for my father to gain acceptance from such a distinguished family. Furthermore, my mother was already engaged to a pilot. At a time when romantic marriages were uncommon, all decisions regarding marriage were made by the family elders. My maternal grandmother was perplexed by my father’s unexpected visits, but knowing that there was very little food in the coal mines, she always ensured he had a meal whenever he came to see my mother.

“Please eat.”

“Thank you.”

Seeing my father eat the food my grandmother served without hesitation, despite her evident disapproval, my mother would secretly observe and say, “What kind of man eats all the rice served to him when he is clearly not welcomed?”

My mother, who resented the idea of an arranged marriage, gradually found herself attracted to my father’s candid demeanor. However, her family’s opposition was too strong for her to express her feelings. In the meantime, my father sent her love letters. She had received many love letters from men, but his stood out as different and special, unlike the others that simply said they liked her.

“Even if we manage to agree on only three out of ten things, I will be grateful for you. I love you.”

She found herself increasingly drawn to his sincere words. However, as my mother’s engagement to the pilot drew near, my grandmother firmly and coldly dismissed my father.

“In ten days, the man my daughter is going to marry will be here. Stop coming to visit. You are ruining my daughter’s marriage.”

But my father didn’t give up.

“Then, just once, let me see her face.”

“Are you out of your mind? Whose wedding are you attempting to ruin? Leave immediately. She’s supposed to be engaged very soon.”

My father had no choice but to leave, unable to say anything more to my grandmother as she stubbornly forced him out. However, the slump of his shoulders as he turned away, like a man who had lost everything, touched my mother’s heart. My mother worried that if she sent him back, she would never see him again. Finally, my mother followed him.

“Leejeong”

The sound of my mother’s voice startled him, but he couldn’t help the smile that spread across his face. Without hesitation, he grabbed her hand and said, “Let’s go.”

She trusted him and decided to follow.

As they went to their room to pack, my grandmother shouted, “If you want to leave, leave empty-handed!”

“Alright, I’ll leave empty-handed.” My mother departed without a single item of clothing, and my maternal grandmother collapsed in shock. Yet my mother’s feelings for him hadn’t changed.

What was it about my father that drew her to him, even though he was much older and from a different family background? Maybe, my father’s letters opened her heart.

But sometimes, I wonder if she yearned for ordinary, everyday happiness. My maternal grandmother, who was prescribed opium to treat an illness during the Japanese occupation, became addicted to it, along with alcohol and tobacco. She often mumbled and spoke to herself, and the neighborhood children would tease her for being mentally ill. In North Korea, individuals with disabilities or mental illnesses are typically relocated to remote rural areas. Consequently, my maternal grandmother, aunt, and uncle were sent to Chuljuri (철주리), notwithstanding their remarkable lineage – my grandmother was an opium addict, and my mother’s sister suffered from polio.

Due to my grandmother’s opiate addiction, my mother spent much of her childhood at her uncle’s house. While her uncle was kind and loving, his wife (aunt) was bossy and abusive. She would make my mother do chores like cleaning and cooking, and she would pinch my mother during meals to prevent her from eating more. Perhaps it was those sorrowful moments of daily life that made her dream of happiness with my father, who seemed so genuine, caring, and diligent.

In the end, my parents got married without the blessing of my mother’s family and began a new life together in a small room in someone else’s house. My mother gave birth to my two elder sisters in that run-down house. After the birth of my eldest sister, my maternal grandmother finally came to visit my mother. However, during her visits, she would frequently let out a sigh and express sadness at the sight of my mother struggling.

Paternal Grandmother’s Reaction

You might be curious about how my paternal grandmother reacted to her eldest son’s marriage. In fact, she was already familiar with my mother.

In North Korea, each village hosts a competition for memorizing Kim Il-sung’s New Year’s Address. One year, both my mother and my paternal grandmother won awards at this event.

Therefore, my grandmother knew my mother as a smart and beautiful young woman, and she was very welcoming and happy about the marriage. When I was about 2-3 years old, my family moved into a larger house and began living with my grandmother.

A Tense Household: Privilege and Indifference

Ironically, and regrettably, the relationship between my mother and my paternal grandmother took a downward turn following my parents’ marriage. My grandmother was, in many ways, a woman of privilege, raised with an air of royalty. Remarkably, she graduated from Tokyo University at a time when most women were not even attending primary school. As a consequence, she contributed little to household chores, delegating the lion’s share to my mother. This arrangement cast a considerable amount of stress on my mom as my grandmother, her mother-in-law, displayed a selfish demeanor, offering little assistance or care toward other family members.

My grandmother spent a significant amount of her time within the confines of her room, delighting in meals prepared by my mom and indulging in her hobby of singing. On the occasional whim, she would knit mittens for us, her grandchildren, yet affectionate interactions or genuine caretaking from her were non-existent in our memories. When she passed away, I was merely seven years old, and candidly speaking, her departure did not leave me deeply grieved.