Beginnings: Unveiling the Story of Aoji Coal Mine

My narrative unfolds in the birthplace of my childhood, the Aoji Coal Mine. Whenever I share my North Korean roots and mention Aoji, I notice an immediate spark of surprise in the eyes of most South Koreans. Some quickly regain their composure, dismissing the revelation with a nonchalant nod and an indifferent “I see.” However, others show a deeper curiosity – “Aoji? The Aoji Coal Mine?” They probe further, “Was there a forced labor camp in Aoji? What were your family’s living conditions there?”

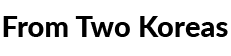

The perception of Aoji, for many South Koreans, used to be mired in misconceptions – an image of brutality, a place unfathomable. Yet, I can confidently say that my second sister, Kumyoung, has played a significant role in recasting this image. It is through her endeavors that many people now recognize that Aoji, too, has been home to good, kind-hearted individuals.

The Community Tapestry: Labor and Life amid the Coal Mines

My family – my parents, oldest sister Kumwha, second older sister Kumyoung, myself, and younger brother Kumchun – made our lives in Aoji until that fateful February in 1997, the moment we dared to escape the grip of North Korea.

Our neighborhood was an intricate tapestry of life and labor, with several coal mines stitched into the landscape beside clusters of homes. Among them, the most formidable was the 6.13 Coal Mine, its name a tribute to a visit by Kim Il Sung himself.

These surrounding coal mines, collectively known as “Aoji coal mines,” were once exploited by the Japanese during the colonial era for resources. The North Koreans carried on this practice post-liberation.

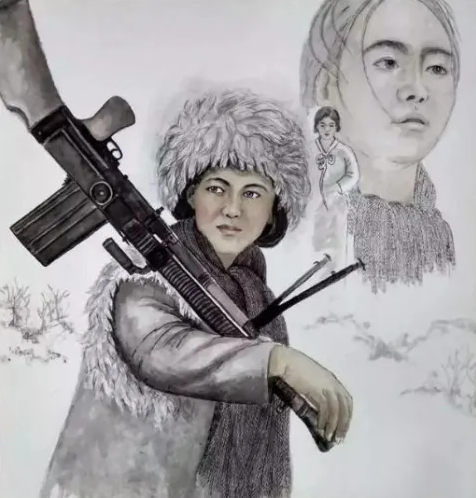

My father spent his days toiling away at the Sunbong Coal Mine, another cog in the wheel of relentless industry. The evidence of his labor was deeply etched into his skin – his hands marked by the rough embrace of coal, chapped and blistered from countless hours of work. He used to wear cotton gloves on his hands and wrap his feet with plastic vinyl beneath his socks for protection. Yet, despite his efforts, winter always left his hands and feet cracked like parched earth.

Most adults in my neighborhood split their labor between the coal mines and farms. Farm workers enjoyed more food access, while miners depended on rations. Thankfully, the Sunbong Coal Mine provided more reliable rations, occasionally sending us sacks brimming with pollock and sardines.

Back in our hometown, the paradox was stark: despite the abundance of mines, coal was a scarce commodity due to its demand for cooking and heating. Households with parents toiling in the farms often struggled to obtain coal, their homes becoming frigid sanctuaries during the cruel winters. Yet, my father’s tireless spirit acted as our bulwark against such scarcity. My father would often come home burdened with a backpack laden with coal, and he would share this precious bounty generously with our neighbors.

The Spirit of Aoji: Community and Resilience

The spirit of Aoji was defined by this shared sense of community, a collective heartbeat that pulsed with generosity. Preparing kimchi, a cornerstone of our culinary traditions, was a communal affair, a social symphony of hands and hearts working in unison. And in times of scarcity, we leaned into this unity, helping each other with essentials like salt or coal. It was this spirit that kept the embers of hope alive, even when the winters grew harsh and the coal fires dwindled.

A Child’s First Glimpse: The Coal Mines Through My Young Eyes

When I was six, my father took me to a coal mine. I was mesmerized by the towering coal piles, the line of minecars, and the machines pulling them from the depths. The sight of people diligently sifting through the coal, the workers loading them into cavernous cars, left me in awe.

Until that moment, my father had always presented himself as a gentle family man, the kind who would effortlessly lift me onto his shoulders and dedicate his spare moments to educating my sisters in the art of music. He gifted my older sisters the ability to strum melodies on the guitar and to decipher the cryptic language of music notes. Though I was still too young to learn the guitar, I looked forward to the day when I could join them in creating harmonious tunes.

Beyond music, he introduced us to the strategic world of Jjanggi (장기), the Korean/Chinese variant of the game of chess. The four of us siblings would engage in friendly yet fierce competitions, each desiring to prove our prowess in Jjanggi. The coveted prize was the chance to play against our father. It was a significant honor, a mark of triumph to play the game with him, having defeated my sisters and brother.

Yet, that day, a different facet of him unfolded before my young eyes. I saw the strength in him, the steel resolve that carried him through days of grueling labor. It was a transformative moment, one where I began to truly comprehend the resilience and fortitude that shaped my father.

Playgrounds Amid the Hollow Caverns: A Child’s Exploration of Abandoned Mines

As I grew older, I would frequently find myself navigating past the abandoned mines that had ceased to yield coal, heading towards the mine where my father devoted his days. Venturing alone past the deserted mines was a daunting endeavor, yet these hollow caverns provided an irresistible playground for my friends and me.

We would lose ourselves in games of hide-and-seek, our giggles and laughter bouncing off the cavernous walls, the echoes reverberating in our ears. The sound of our own voices, amplified and distorted, added an eerie, thrilling undertone to our games. Those deserted mines, simultaneously frightening, exhilarating, and shrouded in mystery, provided the backdrop to our youthful adventures.

During my second year at Elementary School (Known as People’s School 인민학교), we had a field trip to the June 13th Coal Mine. It was much larger than Sunbong, where my father worked, with workers descending vertically to the bottom. When I asked my teacher about the depth, she proudly informed me that it reached 600-700 meters. “The lower regions are filled with water,” she added, “which makes mining coal there a challenging task.”

I remember being awestruck by this revelation, my young mind grappling with the enormity of the fact. “Wow, that’s incredibly deep,” I remember my awe-stricken reaction. I felt a surge of pride for my father and all the fathers laboring in such a remarkable place.

Since arriving in South Korea, I haven’t encountered coal again, yet the memory of its scent lingers. That grateful aroma of coal, once responsible for cooking our meals and warming our homes in North Korea, remains vivid and cherished in my heart.